By Dr SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda

It was only 10 o’clock at night. In an affluent residential suburb of Colombo, a car reversed slowly off the main road. Although it was still early, the road was empty, deserted and dark. The car backed steadily into a side lane. Close by was an abandoned restaurant. Inside there were men singing and swaying to the tune of their own music.

A drunken man weaved slowly to and fro behind the vehicle. The driver got out and told the drunk to move. He was wearing a uniform. The drunk rushed towards him. “Who are you to tell me what do?” He put his hands on the vehicle.

“Take your hands off, don’t touch the car.”

At the sound of rising voices several men came running towards the vehicle. Within minutes, they had surrounded the driver. There were five to six of them. On the other side of the car, another man got out and stood by the door. He too was wearing a uniform. The crowd surged around them. “What did you say?” they demanded angrily.

The two men in uniform stood their ground.

“He asked him to move,” one said. “We told him not to touch the car.”

The crowd became began to swell. People started shouting. “Who are you to tell us what to do? Touch the car? We will do anything we like.” They brushed up against the driver, jostling him. One or two even touched his uniform. Putting their hands on the car, they peered inside the half-open windows. The two soldiers stiffened and held their ground. They did not react.

A big made man appeared from within the crowd. His face too was flushed. “What are you all doing here? Who do you think you are?” Hands on hips, he stood right in front of the car. The soldier on the other side spoke directly to him. “Look, we are just trying to do our job. The vehicle is our responsibility.” The man leaned in. “Who is in the car?”

“Our officer is in the back.” The man peered inside. We remained silent. The officer did not move. The seconds of silence calmed the air.

The man spoke into the car. “Sorry sir, we don’t want trouble. I was in the forces too.” He nodded to the other men. They stepped back. Slowly the soldiers got back into the car and we drove away.

It had been a moment waiting to happen. A deliberate attempt to provoke.

The officer explained. “We are now targets. We have been warned to take care when we use our vehicles. We have been told not to react.”

I wondered to myself, “What if they had reacted?”

Unlike India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, Sri Lanka has never had a separate military culture. There are no cantonments. The military do not live in separate residential areas and their children do not go to special schools. The vast majority of Sri Lanka’s servicemen live cheek by jowl with their neighbors. Like their neighbors, their families have no petrol and no diesel, no gas to cook, their lights are cut for hours and their children are not going to school. Like the rest of society, they are angry, resentful and worried.

“Our own families are suffering. We all have to go home to our villages.”

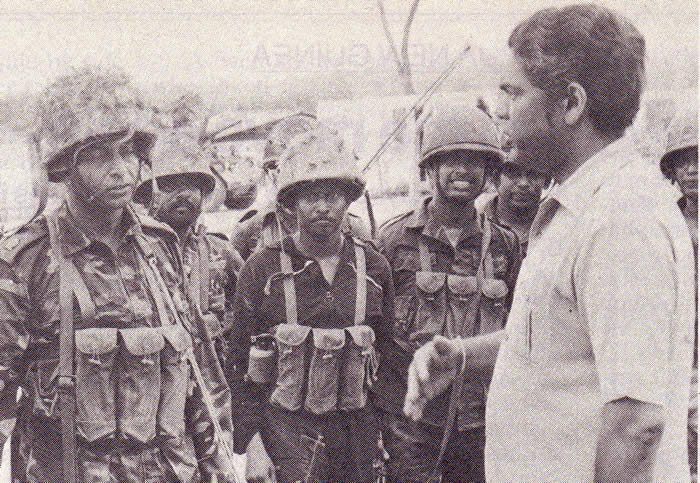

The events of the last few months have seen a complete transformation in the position and perception of the armed forces in Sri Lanka. The end of the 30-year conflict with the Tamil Tigers saw the military acclaimed as “Ranaviru” or “Golden Heroes.”

During the height of the pandemic (2019-2021), the forces had earned public trust and respect as the most effective arm of government. Erecting hospitals and quarantine centers at Caesar speed, they revolutionized the chaotic vaccination process. By the end of 2021 nearly two thirds of the population had been immunized.

In the aftermath of the April Bombings of 2019 the armed forces had been the ultimate guarantor of law and order. Swiftly and effectively, they ensured there was no widespread retaliation against Sri Lanka’s Muslim community. However, in recent months the implosion of the economy has completely transformed their position.

In April and May 2022, the public discontent which had been simmering for months finally erupted. On the 1st of April protestors attempted to storm President Gotabaya Rajapaka’s home. On the 9th of May supporters of Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa emerged from the premier’s residence and attacked anti-government demonstrators.

This set off an outpouring of rage across the country. There was rioting on the roads, vehicles were set alight and the homes of members of the ruling party burned to the ground. The level of anger was such that even the Leader of the Opposition, Sajith Premadasa, was attacked when he tried to reach the scene.

Cowed, discredited and often powerless, the police proved incapable of controlling the mounting anger. In the days following the rioting, a Detective Inspective General of Police was assaulted in front of the cameras. Finally on the 12th of May after two days of mayhem, the army were brought in and given orders to shoot. Since then, an uneasy calm has prevailed.

Sri Lanka has reached a stage where the armed forces have become the only guarantor of law and order, life and private property. A military is defined by its power to enforce. In this atmosphere the military cannot enforce, for the fear of the reaction and the repercussions. The question constantly posed by international journalists and news channels is this: “Is a military takeover looming?” This refrain has been widely repeated by some civil society groups.

What is looming is far more dangerous. The core of the problem lies with authority. The uniform embodies an authority which has lost legitimacy. As long as this situation prevails, law and order cannot be enforced or guaranteed. Unless legitimacy is restored in some way or another, this could lead to a collapse of morale in the last bulwark of law and order. When that happens Sri Lanka will have no government left.

“Which officer is going to give the order to shoot on our own people?”

“What are we to do? So far there have been no events. What will happen when they start attacking us, and setting fire to our vehicles?”

A historian by training, Dr. SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda is an art historian, academic, writer and award-winning film maker. The author of several major publications on the art and culture of Sri Lanka, he is also a regular speaker, lecturer and advisor in South Asian and Strategic Studies, whose work has been published in the national and international press, academic books and military journals. This article was based on actual events and actual dialogues. It includes quotations from officers and soldiers on the ground.

Factum is an Asia-focused think tank on International Relations, Tech Cooperation and Strategic Communications based in Sri Lanka accessible via www.factum.lk