By Shiran Illanperuma

From October 22 to 24, the 16th BRICS summit was held in Kazan, Russia. Alongside the core group members of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, this year saw the formal addition of Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates. During the summit, another 13 countries, including Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Nigeria, Uganda, Cuba, and Bolivia, became partner members.

This year, Sri Lanka joins a growing list of countries from the Global South that have applied to become members of BRICS. Foreign Secretary Aruni Wijewardena led the Sri Lankan delegation to the Kazan summit. Meanwhile, Foreign Minister Vijitha Herath has written to his BRICS counterparts for support in joining.

The Kazan summit occurs in the context of an increasingly tense global situation, characterised by the ongoing Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza, the NATO-led proxy war in Ukraine, and the US-led new Cold War on China. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech at the summit describes a world descending into “the abyss of disorder and chaos.” Referencing the Russian novel What is to be Done? (also the title of a key text by Vladmir Lenin), Xi summarised the spirit of BRICS:

“The more tumultuous our times become, the more we must stand firm at the forefront, exhibiting tenacity, demonstrating the audacity to pioneer and displaying the wisdom to adapt. We must work together to build BRICS into a primary channel for strengthening solidarity and cooperation among Global South nations and a vanguard for advancing global governance reform.”

The message is clear. BRICS stands for peaceful development and cooperation, against the political domination and unilateralism that have characterised the US-led post-World War II order.

A world in disorder

Ironically, the acronym BRICS originates from a 2001 report by a Goldman Sachs document that predicted a shift in economic power that would necessitate the G7 to open up to more members from the Global South. However, there is a case to be made for BRICS being the product of a much longer historical cycle of revolutions and national liberation struggles against Western imperialism.

A line can be drawn from the awakening of Russia and China in the early 20th century to the Arab revolt, the Indian independence movement, the wave of African liberation struggles, and the Non-Aligned Movement to the present multipolar zeitgeist. BRICS is merely the latest manifestation of this long arc of history.

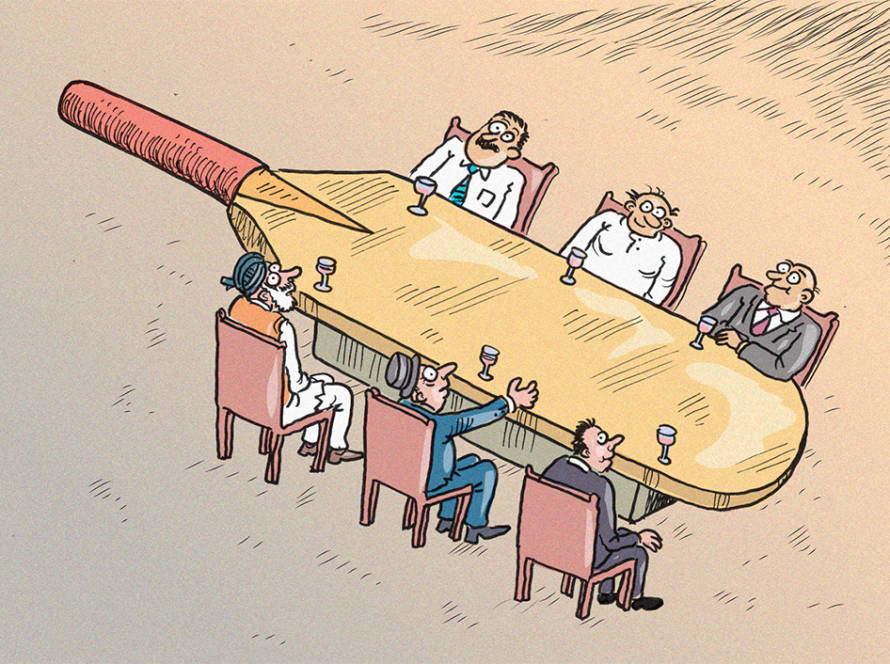

Nonetheless, the organisation remains rife with contradictions. India remains a member of the QUAD and a key node of the US-led Indo-Pacific Strategy. Post-Apartheid South Africa has been completely immobilised by neoliberalism. Brazil has blocked Venezuela’s application to join the group.

The UAE is deeply embedded in the US financial and military architecture, being one of the first Arab countries to establish diplomatic ties with Israel. China and Russia remain the militant core of the group and the countries with the most resources and will to power to reshape the global order.

Yet there are objective economic and geopolitical factors that force countries with diverse and sometimes contradictory political projects to converge on a common platform for cooperation. The US has increasingly isolated itself through protectionism, the prosecution of destabilizing hybrid wars, the weaponisation of its control over the global financial system, and its monopoly on printing the world reserve currency.

Meanwhile, the global majority still grapples with the scourge of war, poverty, and underdevelopment. It is this global majority’s demand for peace, productivity-enhancing technology, and financing for investment, that is the material basis for BRICS.

BRICS and the future of Sri Lankan industrialisation

Sri Lanka could very well be a poster child for the disorder and chaos of the international order. In many ways, the country’s internal instabilities are conditioned by external factors. First, imported commodity price inflation following the war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia hit a country already battered by COVID-19 and the collapse of tourism and remittances.

As Israel, with the support of the West, threatens to trigger a regional conflict in West Asia, a prolonged period of commodity price inflation would be just as devastating for the Sri Lankan economy.

Second, Sri Lanka’s external debt default and restructuring process highlight the rigged nature of the global financial architecture and the Bretton Woods Institutions. The lack of a global system for recycling surpluses and providing concessional finance for productive infrastructure and industry is strongly felt by countries like Sri Lanka.

Deflationary policies imposed by the IMF and World Bank have been antithetical to industrialisation and economic growth. Since its first report on the country, the World Bank has sought to divert the attention of local policymakers away from large-scale industry and towards various cul-de-sacs, including peasant colonisation, services, and micro-entrepreneurship. As if any country has been able to develop along these lines.

By contrast, the fledgling New Development Bank creates new possibilities for development financing, including in currencies other than the dollar. The core members of BRICS, including Russia and China, know full well that sovereignty can only be built on a foundation of large-scale industry. Through BRICS, there is an opportunity to combine new financing mechanisms and growing technical expertise from the Global South to jumpstart start industrialisation in Sri Lanka.

BRICS contains a number of industrial initiatives that Sri Lanka could stand to benefit from, including the BRICS Partnership for the New Industrial Revolution (PartNIR) which was introduced in 2018. The Kazan declaration suggests that the PartNIR Advisory Group has created working groups on sectors such as chemicals, mining and metals, and pharmaceuticals. These are all the value-added industries that Sri Lanka should be looking at in a drive towards industrialisation in the 21st century.

Finally, President Xi’s speech in Kazan highlighted China’s willingness to expand collaboration with BRICS member states on green industrial chains. China currently dominates the green energy sector, including in the processing of rare earth minerals and the manufacture of batteries and photovoltaic panels. As a member of BRICS, Sri Lanka could leverage Chinese expertise in this sector to enhance the value addition of domestic resources such as graphene and join the green energy industrial chain.

BRICS is still very much work in progress. Its outcome is not written in stone. In the spirit of Bandung, Sri Lanka should be playing an active role in shaping the outcome of BRICS and taking its rightful place in world history.

See also: Factum Perspective: Are China and Russia Imperialist?

Shiran Illanperuma is a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He holds an MSc in Economic Policy from SOAS University of London. He can be reached at shiran.illanperuma@gmail.com

Factum is an Asia-Pacific-focused think tank on International Relations, Tech Cooperation, and Strategic Communications accessible via www.factum.lk.

The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the organization’s.