By Vinod Moonesinghe

We bear witness to a period of accelerated global transformation, with the rise of the East and the relative decline of the West reshaping the global political and economic landscape, benefitting the Global South. China, whose rapid economic growth and expanding influence play a pivotal role in this new era of global realignment, stands at the forefront of this shift.

The emergence of New China under Mao Zedong intensified with the introduction of Deng Xiaobing’s reforms. Under Xi Jinping, we see China’s remarkable economic ascent, lifting millions out of poverty and transforming it into a global industrial powerhouse.

The “Red Dragon” lies at the cusp of a qualitative change, as it asserts itself increasingly in international affairs, from trade and technology to diplomacy and global governance.

Transition

Increasing multipolarity – in which several key players share power, replacing domination by a single hegemon – marks the alteration of the geopolitical terrain. This transition requires rethinking of global governance structures and a more inclusive approach to international cooperation.

As a leading global power, China bears substantial responsibility for reshaping international relations, balancing its national interests with the need for global stability and development. This obligation encompasses issues such as climate change, global health, and peacekeeping. China’s actions in these areas will not only determine its own future but will also have profound implications for the entire world.

On the other hand, we have seen the decline of the West, accelerated by the long crisis which began as the Global Financial Crisis in 2007-8. A series of challenges, including economic stagnation, political polarisation, and growing social divisions have weakened these powers and eroded their influence, particularly in Europe and North America.

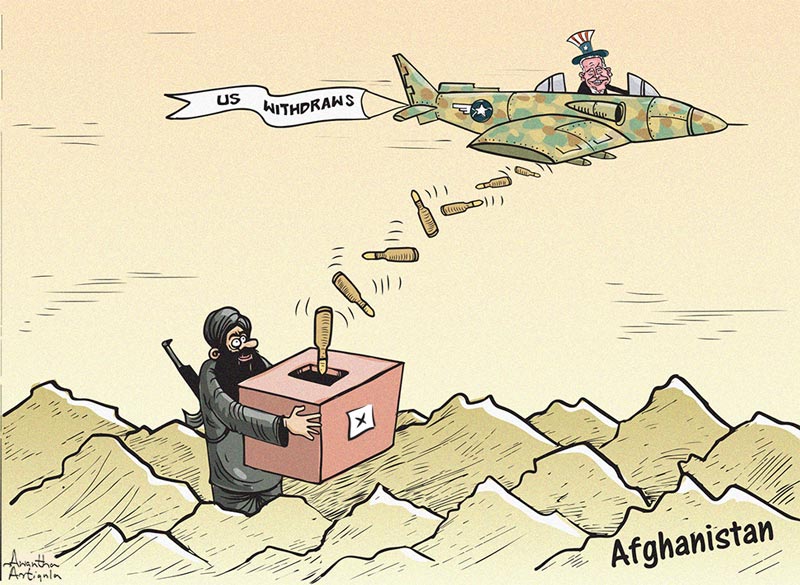

As these countries grapple with internal crises, their ability to shape global affairs diminishes. However, they continue to attempt to do so by promoting conflict, not just between countries but also internally. The consequences, including the genocide in Gaza, the NATO-provoked war in Ukraine, sanctions against Cuba, Iran, Russia and Venezuela, interventions across Africa and the trade war against China, all bode badly for global peace, stability and economic development.

China-US relations are important factors for global stability. However, to counter increasingly erratic US behaviour, China must focus efforts on Global-South-led multilateralism. The US Indo-Pacific strategy aims to reshape in its favour the emerging production networks in Asia, potentially leading to differing perspectives among neighbouring countries. Peace and stability in the region are first and foremost the responsibility of those in the region itself, irrespective of size and power.

Hybrid warfare

Modern conflicts are no longer confined to traditional military confrontations, but encompass broad arrays of non-military tactics, including economic sanctions, media manipulation, cyberattacks, and other forms of asymmetric warfare. The USA and its allies are adopting these strategies increasingly to influence and change governments, especially those that do not align with their interests.

This “hybrid warfare” seeks not just to weaken states militarily but to erode their democratic processes and impose governance that serves the interests of a global elite. The impact of these conflicts extends far beyond the political sphere, often resulting in widespread suffering for the populations caught in the crossfire. The US and its allies flexed their muscles in the South Asian region, leading to hybrid warfare against Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh, securing “regime change” in all three nations.

The West has networks of proxies and advocates embedded within national systems, throughout state bureaucracy, judiciary, and civil society. These arise through patronage, openly through funding for non-governmental organisations, less obviously through scholarships, funded conference invitations, study tours and junkets. Aided projects usually push Western agendas.

The West also provides funding for social media influencers, while diplomats and funding agency staff socialise regularly with influential persons. In this environment, creating an anti-Chinese, pro-Western ambience may be done relatively easily, by influencing the intelligentsia, government officials and even the judiciary.

Century of humiliation

However, China’s foreign policy establishment has, hitherto been virtually powerless against this approach. This has its roots in China’s history. The “Century of Humiliation,” the period from the opening of the First Opium War in 1839 to the establishment by of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, has profoundly shaped China’s foreign policy.

Marked by foreign invasions and subjugation from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century, this era instilled a deep sense of national humiliation and a desire to restore China’s sovereignty and dignity.

China maintains a strong emphasis on maintaining sovereignty and resisting foreign influence, as witnessed by its stance on such issues as Taiwan and Hong Kong. It has a more assertive foreign policy, particularly where it seeks to protect its territorial claims and maritime rights, as in the South China Sea.

At the same time, Beijing is sensitive to foreign criticism. It uses economic tools, such as trade and investment, to build influence and counterbalance perceived threats from Western powers. These factors contribute to a foreign policy that is both defensive and proactive, aiming to ensure China’s security and global standing.

However, foreign policy principles rooted in the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, constrain Beijing. These include mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. This has, hitherto, prevented the implementation of “unofficial” strategies similar to those the West deploys.

“Deepening Reform Comprehensively”

The idea of “Deepening Reform Comprehensively” emerged as a strategic initiative under the leadership of Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the CPC, as part of the broader agenda to modernise China and realise the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation.

This initiative recognises that reform is an ongoing process, requiring continuous adaptation and innovation to address new challenges and opportunities. It involves a multi-faceted approach that encompasses economic, political, cultural, social, and ecological reforms, aiming to build a more robust, equitable, and sustainable society by addressing systemic issues and enhancing governance mechanisms.

Economic reforms focus on transitioning from a growth model driven by investment and exports to one driven by domestic consumption, innovation, and high-quality development. Political reforms emphasise improving governance, promoting rule of law, and enhancing the CPC’s leadership capacity.

Cultural and social reforms aim to strengthen cultural confidence, promote social equity, and improve the well-being of the population. Ecological reforms focus on building an environmentally sustainable development model in line with the concept of “ecological civilisation.”

Xi’s concept of “Deepening Reform Comprehensively,” has become key to China’s socio-economic and political transformation. While protecting sovereignty, this vision compels China to deepen reforms, while advancing peaceful modernisation through innovation.

It commits to upholding shared human values and a globally shared future, fostering global cooperation and resolving international disputes via dialogue. It promotes a multipolar world and inclusive globalisation, guided by such initiatives as the Global Development, Security, and Civilisation Initiatives. It can provide a foundation for countering hybrid warfare.

Response to hybrid warfare

China can respond to the West’s hostility on two levels. At the level of statesmanship, it can take the lead in rewriting the framework for multilateralism, investment, trade, diplomacy, and conflict mediation, respecting the sovereignty of all and ensuring peaceful and balanced development.

In this, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) must play a major role, finding a just way to recycle global surpluses, avoid debt traps, and provide equitable development. The Global South needs productive investment to aid the industrialisation process and help build national economies and industrial proletariats.

Unfortunately, slowing financial flows from China to BRI projects and increasing debt repayments to bondholders by the Global South have caused serious financial issues in BRI partner countries. The latter need technical assistance in development planning and ensuring proper management of BRI assets, and more coordination between them to enhance complementarity of assets.

Whereas the Global South has tended to focus on GDP-centred economic growth, China should emphasise people-centred development to achieve human and ecological goals. It must take the lead in ensuring global peace. Such mechanisms should go beyond the Western model of counter-insurgency and address the root cause of terrorism. Cooperation must extend to combatting hybrid warfare.

For centuries, the West has imposed its cultural and civilisational values upon the Global South. In its latest iteration, “McWorld”, it seeks to create cultural uniformity corresponding to world hegemony. Cooperation should focus on furthering respect for diversity, common human values and cultural exchanges, to advance mutual learning and understanding while opposing the imposition of one nation’s values.

Country-level responses

At the level of individual countries, China needs to do more work to enhance its soft power and communicate its ideas on a people-to-people basis. In this regard it lags far behind the Western powers, from whose book it must take a page.

Beijing needs to support progressive forces, in their efforts to establish ideological hegemony in both intellectual and political fields. Support to the grassroots could be channelled through a network of think tanks, advocacy and developmental non-governmental organisations, carrying out progressive-oriented projects.

China must assist in building a system of linkages between progressives, bureaucrats and civil society, through channelled scholarships, conference invitations, and study tours. At the same time, it must ensure that support does not go to groups or individuals propagate the view that China is a colonising power.

“Deepening Reform Comprehensively”, especially where applicable to global affairs, can provide an intellectual and moral basis for a shift in Chinese foreign policy, from passive non-interference to pro-active, non-intrusive intervention. Such a change may be vital to preserve peace, development and ultimately, the planet.

Vinod Moonesinghe read mechanical engineering at the University of Westminster, and worked in Sri Lanka in the tea machinery and motor spares industries, as well as the railways. He later turned to journalism and writing history. He served as chair of the Board of Governors of the Ceylon German Technical Training Institute.

Factum is an Asia-Pacific focused think tank on International Relations, Tech Cooperation, Strategic Communications, and Climate Outreach accessible via www.factum.lk.

The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the organization’s.