By Shiran Illanperuma

The NATO-Russia conflict playing out in Ukraine has brought to the fore long-simmering international tensions. These include the role of the US Dollar as the global reserve currency, and the power of the US government to unilaterally exclude nations that challenge its dominance from international trade, by sanctions and bans from international payment systems like SWIFT.

US economist Michael Hudson likens recent US financial sanctions on Russia to “shooting themselves in their own foot”. They are in reality providing Russia – the 11th largest economy in the world and home to the largest natural gas reserves in the world – a powerful incentive to find alternative mediums of exchange and payments systems so as to conduct trade. In addition, US sanctions signal larger economies like China toward the growing need to diversify away from dollar-denominated assets in order to manage economic and geopolitical risks.

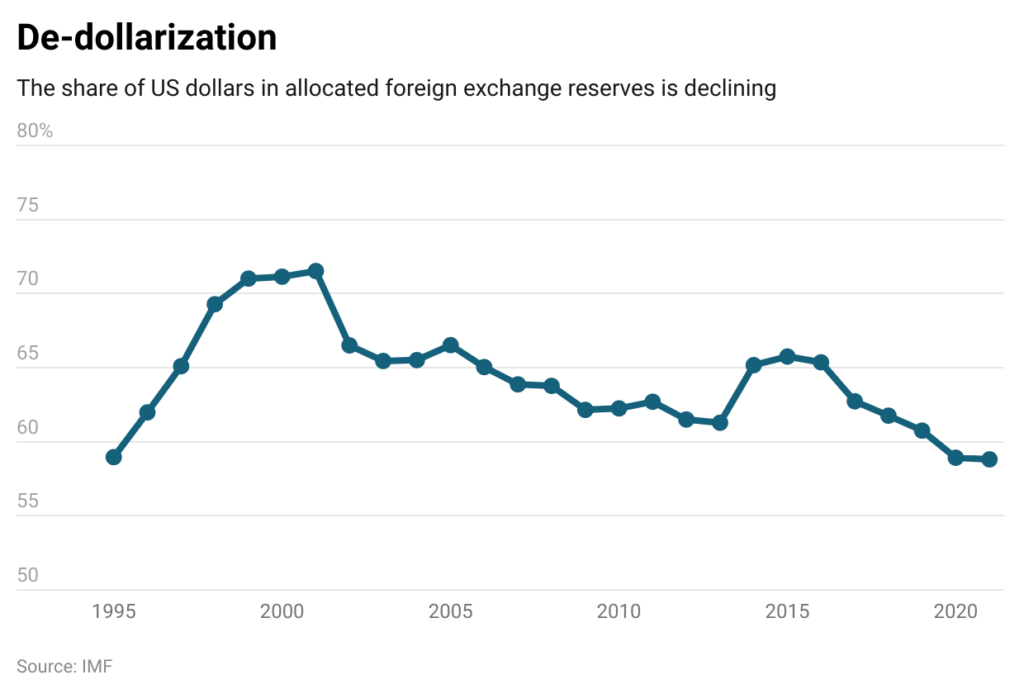

Russia and China are the two major countries leading what is often tagged, “de-dollarization”. In 2019, Russia halved the dollar-denominated share of their forex reserves, opting to expand Euro, Yuan and gold holdings, which now comprise around 90% of Russia’s reserves. Meanwhile, China has been its US treasury holdings since 2015, opting instead to lend to developing countries through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and accelerate Eurasian economic integration. By 2021, IMF data showed that the US Dollar share of global reserves had dropped to its lowest levels since 1995. According to a 2021 survey by London-based think tank OMFIF, 30% of central banks planned to increase their holding of Yuan, while 20% planned to reduce their holdings of the US dollar.

China today is the world’s largest importer and exporter, as well as a larger creditor than the IMF and World Bank. This makes the Chinese Yuan (or Renminbi, ‘people’s currency’) the most poised to take over as the world reserve currency in the next business cycle. It remains to be seen whether Chinese policymakers wish to go down this path and risk ending up like the US – which promoted its currency to world reserve status at the cost of deindustrialization, financialization, and high inequality at home. It is perhaps more likely that a reserve currency based on a basket of currencies of major economies may be more beneficial for global stability and multipolarity.

PetroDollar at risk

In 1971, the USA unilaterally decided to abandon the gold standard and move to fiat currency in response to high inflation and their trade deficit. By 1974, the US struck a deal with OPEC to make the US Dollar the standard currency for global trade in oil. This gave rise to what is now known as the petrodollar, as global oil transactions helped prop up the value and stability of the US Dollar despite the USA’s own yawning trade deficit. This also gave the US power to print large amounts of its currency to prop up financial markets while outsourcing manufacturing.

However, this status quo, too, is on the verge of change. For over six years now, China and Saudi Arabia – the world’s second-largest producer of crude oil – have discussed the possibility of conducting oil transactions in Yuan. This is less outlandish than it may first sound, as Saudi Arabia’s biggest trade partner is China, accounting for over 20% of imports and exports. In 2017 the central banks of Russia and China agreed to conduct crude-oil transactions in Yuan. More recently, India and Russia have explored a SWIFT alternative and a rupee-ruble payment scheme to trade oil. Adding to this geopolitical shift is Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ultimatum that “unfriendly countries” pay Russia in rubles for gas. This could have vast implications, as 41% of Europe’s gas requirement is imported from Russia (the now-cancelled Nordstream 2 pipeline would have doubled Russian gas shipments to the European Union).

To make matters even worse for the petrodollar, the world is also on the verge of an energy revolution that could drive the next business cycle. Usually, new business cycles bring with them a radical change in energy infrastructure. Global capitalism has shifted from steam to coal to oil and gas, and the future appears to be a mix of dynamic renewable energy and stable nuclear energy. The current spike in fossil-fuel prices will only accelerate this shift, endangering the petrodollar even further.

Why Sri Lanka can’t de-dollarize

Sri Lanka today is in a crisis that is dollar-denominated. As a former plantation economy, Sri Lanka specializes in the production of a handful of agricultural products. Deteriorating terms of trade in the 1950-60s are the origins of the country’s trade deficit, which in turn pushed the country into to external debt. While the Covid-19 pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine have certainly exacerbated the problem through losses in tourism revenue, and soaring prices of grain, energy and logistics, these external shocks have only revealed pre-existing weaknesses in Sri Lanka’s still woefully unindustrialized economy.

With de-dollarization gaining momentum, one could ask why Sri Lanka needs US Dollars at all. Why can’t we simply switch to Yuan? Why can’t we find a rupee-ruble mechanism to buy oil at a discount from Russia? Indeed, Sri Lanka has strong diplomatic ties with the de-dollarizing bloc. The former Soviet Union provided much of the hardware that set up Sri Lanka’s heavy industry in the 1950s and 1960s. China has financed and built much of Sri Lanka’s contemporary road, port and energy infrastructure. Sri Lanka’s biggest import origins are China and India. The problem lies, not in where Sri Lanka imports are from, but where it exports to.

Sri Lanka’s largest export markets are the USA and the EU. This is partly because the country’s only significant manufacture – garments – was developed through the Multifiber Agreement, making it uncompetitive and dependent on Western markets. This garment sector, while being a major foreign-currency earner, also represents a geopolitical weakness for Sri Lanka, as the country cannot maintain strategic autonomy without the threat of losing perks such as the GSP+ which keeps it locked into Western markets and the US Dollar.

Sri Lanka’s exports to the likes of Russia and China are still predominantly agricultural products, such as tea and coconut. To diversify its reserve currency basket, Sri Lanka would have to first diversify its export manufactures, which in turn requires a progressive industrial policy to develop its domestic manufacturing. Sri Lanka must boost two-way trade within Eurasia, for de-dollarization to be a serious option. Failing which, the country risks losing an opportunity to be an innovative first mover in the growing international trend of de-dollarization that is likely to drive the next business cycle.

(The writer is Editor of Biznomics magazine and a Research Analyst at Econsult Asia, a financial & management consultancy firm)

******

Factum is an Asia-focused think tank on International Relations, Tech Cooperation and Strategic Communications based in Sri Lanka accessible via www.factum.lk