By Sachintha Pilapitiya

Sri Lanka has often stressed its principle of “friendship towards all, enmity towards none” in its diplomacy. In 2024, under two ideologically contrasting governments, Sri Lanka reflected the possibility of maintaining this foreign policy goal intact.

In this article, I conduct a short review of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy in 2024, followed by its potential to continue its balancing act with multilaterals, major powers, and middle powers. I conclude with a suggestion as to how integrating a “laying low” strategy to its “balancing act” will benefit Sri Lanka in 2025. For conciseness, this article will provide a general overview of potential strategies and will not go into detail on specifics.

2024 in Review

2024 began under the leadership of President Ranil Wickremesinghe, whose claim that “’I am not pro-Indian or pro-Chinese; I am pro-Sri Lankan” in late 2023 symbolized his strategic foreign policy goals.

In 2024, Sri Lanka’s foreign policy was marked by significant developments each month, reflecting its strategic positioning between major powers and addressing internal challenges. Overall, however, it avoided biases and volatile changes in alignment that shaped the country during the previous few regimes.

Throughout the year Sri Lanka’s foreign policy was clearly concurrent with its domestic economic needs. Sri Lanka managed to maintain good relations with the IMF, successfully passing its reviews despite a change in regime.

Maintaining good relations with a multilateral institution (largely Western) is no easy task, especially for a left-leaning regime, and therefore should be considered an achievement.

Similarly, progress was made coordinating debt restructuring with diverse groups such as the Paris Club members, China, and private creditors. Much more work has to be done on this front this year, however, giving more emphasis for continuing a balanced relationship with all.

Multilaterals

Though still a concern, the new government has largely enabled Sri Lanka to move beyond the human right allegations that barred officials in previous regimes from fully dealing with several established international organizations and western governments.

While still committing to international laws, Sri Lanka can now channel its full energy on optimizing economic opportunities facilitated through these organizations. However, as Sri Lanka gains access to a range of financing options from a range of institutions from the World Bank to the Asian Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure and Development Bank (AIIB) to improve the standards of living of its people, it must be approached with fiscal constraints and nationally planned development goals in mind.

Finally, President Wickremesinghe’s actions in 2024 also reflected how small island nations such as Sri Lanka can play a leading role in global initiatives such as dealing with climate change. Innovative financing tools provided by these forums (such as debt for development swaps) should be explored through partnerships with institutions such as the Green Climate Fund and Global Green Growth Initiative.

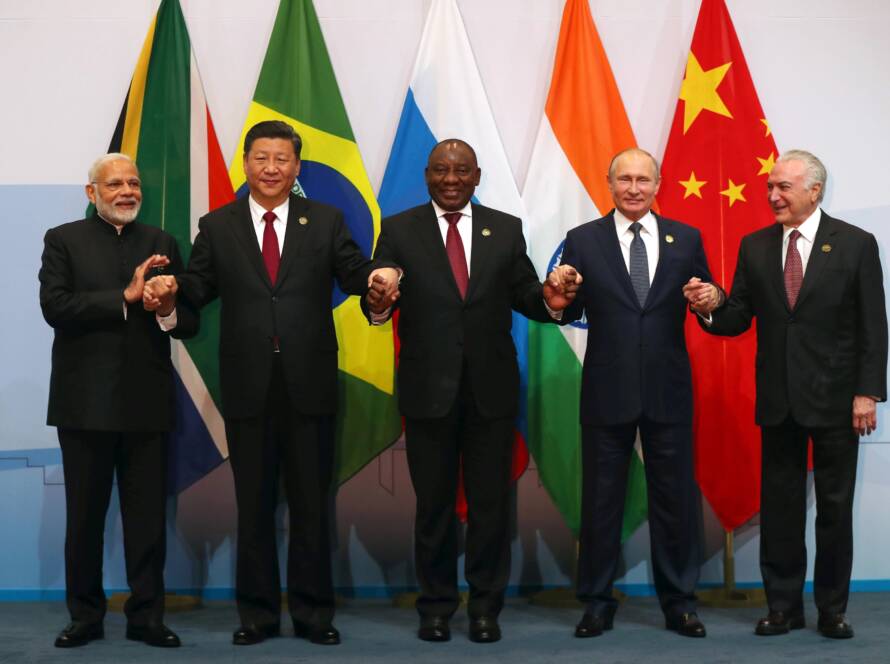

Major Power Relations: A Balancing Act

The year-end highlight for Sri Lanka’s 2024 foreign policy was President Dissanayake’s first overseas visit to India.

As India doubles down on its “Neighborhood First” policy, and other neighbors such as Bangladesh move further away from India, Sri Lanka can strengthen its ties with India to bolster India’s support, both economic and geopolitical. Given the Trump – Modi “‘”bromance”’,” wooing the US through India should be a key goal in Sri Lanka’s balancing act.

President Dissanayake’s second foreign visit to Beijing reflects Sri Lanka’s intention to maintain friendly relations with China. Whilst this will essentially be part of the balancing act, Sri Lanka could utilize a “laying low” strategy here to optimize its relationship.

That is to keep a low profile as it gets back on track, avoiding attention through large scale projects that are both unsustainable and draw undue and at times unfair international attention. China’s own transition to facilitating “small and beautiful” projects in its BRI expansion aligns with such an ideology.

In this context, as high tariffs between great powers are expected to soon materialize, Sri Lanka has much to learn from countries such as Vietnam who have established themselves as “‘re-export” centers, benefitting from the provision of services as a middleman in global trade. Sri Lanka’s strategic positioning clearly allows for this.

Furthermore, adding value to its current exports and investments should be a goal of both the Sri Lankan government and its enterprises to remain competitive.

Middle Power Relations: Laying Low

Crucial in facilitating the laying low strategy is Sri Lanka’s relations with middle powers. For example, countries such as South Korea and Japan were some of the first countries that provided development assistance to the new government and have been some of the most active partners since then.

Mainly grants from these countries have been channeled towards productive investments. Furthermore, Sri Lanka can facilitate win-win relations with these countries, for example through its large migrant workforce that supports especially the aforementioned two countries going through their own economic hardships caused by declining demographics.

Similarly, strengthening its ties with Middle-Eastern countries should be a clear goal in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy for 2025, as past wounds (forced cremations during the pandemic) require healing and Sri Lanka has symbolic capacity to show its support as the region faces difficulty (for example the Children of Gaza Fund organized by Sri Lanka).

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s post war foreign policy has mainly been based on its development needs. Whilst this need continues, a new government provides a fresh start to optimize its economic diplomacy. While its recent recruitment of a new batch of foreign service officers reflects a hopeful return to professionalism, the Sri Lankan foreign service has limited fiscal and human resources to take on economic diplomacy by itself.

Instead, it can facilitate and support Sri Lanka’s under-appreciated local multinationals (ranging from companies such as Brandix to Hayleys and Dilmah) as well as up and coming brands such as Spa Ceylon, Carnage, and Ministry of Crab, to do the talking and bring home the bucks.

Such efforts can remind all that foreign policy is not only about taking, but also giving. Though small, Sri Lanka has on countless occasions soothed global tensions and in an era of hegemonic transition and great power competition, it is important now more than ever.

Sachintha Pilapitiya is a Schwarzman Scholar at Tsinghua University, China, and an Economics graduate of New York University Abu Dhabi. He can be contacted at sachipila@gmail.com.

Factum is an Asia-Pacific focused think tank on International Relations, Tech Cooperation, and strategic Communications accessible via www.factum.lk.

The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the organization’s.