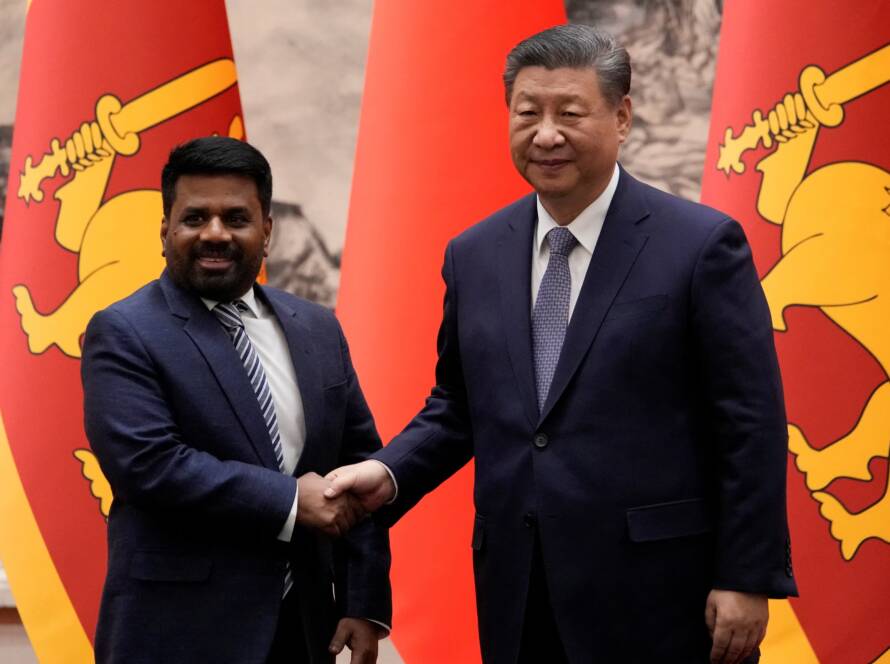

Vinod Moonesinghe

The Tang dynasty (618–907) became a golden age for Chinese poetry, sculpture, and Buddhism. Its capital, Chang’an (modern Xi’an), the starting point of the Land Silk Road, grew into an international hub with traders and embassies from Central Asia, Arabia, Persia, Korea, and Japan. The economy thrived, with rural markets connecting to Chang’an and other major cities. Foreign music and dance gained popularity.

Buddhism flourished, with new translations of scriptures brought to China by traveller-monks such as Xuanzang (602-664). Like his fourth-century predecessor Faxian, Xuanzang worried over incomplete and misinterpreted Buddhist texts and about the conflicting Buddhist doctrines arising from various Chinese translations. To address these issues, he sought to obtain original, untranslated Sanskrit texts from India.

In 629, Xuanzang set out on a 17-year journey to India and back. Although he intended to follow Faxian to Sri Lanka, troubles there caused him to break his journey at Kanchipuram. He returned to China laden with 657 Mahayana and Theravada Buddhist texts, over a hundred relics and seven statues of the Buddha. Welcomed and honoured by the Tang emperor, who encouraged him to write an account of his travels, Records of the Western Regions, he withdrew to a monastery, dedicating himself to translating Buddhist texts until his death

The legend

The impact made by Xuanzang cannot be gainsaid. His translations to Chinese of the Buddhist texts he brought, and his writings based on what he learnt in India – particularly his Cheng Weishi Lun, a long essay on Yogachara (the doctrine of consciousness) – influenced Mahayanist Buddhism profoundly.

His influence gave him saintly status in China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam. He is venerated in temples such as the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, Xi’an (which he founded) and the Xuanzang Temple, Taichung.

His journey along the Silk Road inspired many legends, culminating in the Ming dynasty novel Journey to the West (Xi You Ji). In this great classic of Chinese literature, written by Wu Chengen, his fictional counterpart Tang Sanzang, a reincarnation of the Golden Cicada, is a disciple of Gautama Buddha.

Like Xuanzang, Tang Sanzang sets out on a quest to obtain the Buddhist scriptures from India. The story focuses on Sun Wukong, who gains immortality and causes chaos in Heaven before being subdued by the Buddha. Promised freedom by the Bodhisattva Guanyin, he escorts Tang Sangzan, alongside a pig-spirit, a sand-spirit and a dragon-horse.

A jaded mandarin retired from the Ming civil service, Wu Chengen crafted Journey to the West in a colloquial style, combining folklore with the historical account of Xuanzang’s journey. The novel is an allegory and a satire of Ming society, particularly targeting the state, clergy, and bureaucracy. Sun Wukong and his companions embark on adventures marked by their human-like flaws, offering a stark contrast to modern superhero perfection.

Sun Wukong

Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, is a beloved figure, affecting Chinese culture profoundly. His character has also had a broader global cultural impact, through translations of Journey to the West by Arthur Waley and by Anthony C. Yu, and through the cult TV series Monkey.

It has motivated numerous literary, artistic, and dramatic works, such as Cordwainer Smith’s science fiction novel Norstrilia, many graphic novels and modern Japanese manga and anime; over 30 films and 14 television series, such as The New Legends of Monkey and Into the Badlands; and video games like League of Legends and Enslaved: Odyssey to the West.

Sun Wukong became the central character of Journey to the West through a combination of mythological and folkloric traditions. One theory, supported by scholar Meir Shahar, connects him to the Lingyin Si monastery in Hangzhou, founded by the Indian monk Huili on Feilai Feng mountain. This mountain, home to gibbons who coexisted with monks, inspired early legends about magic monkeys, bearing striking similarities to Sun Wukong.

Feilai Feng, meaning “the peak that flew here,” is linked to Vulture Peak (Gṛdhrakūṭa) in Bihar, where the Buddha taught. In Mahayana Buddhism, Vulture Peak evolved into a symbol of spiritual attainment, and in Journey to the West, Tang Sangzan and Sun Wukong achieve Buddhahood there.

A legend holds that Huili and a monkey disciple travelled from Vulture Peak in India to Hangzhou, where they recognized Feilai Feng as its counterpart, suggesting a direct link between Huili’s monkey and Sun Wukong.

Hanuman

Another theory, championed by Hu Shih, suggests the South Asian monkey deity Hanuman as inspiration for Sun Wukong. The similarities are remarkable: Sun Wukong’s chaotic attack on the Jade Emperor’s celestial city mirrors Hanuman’s airborne assault on Ravana’s city of Lanka, and both can leap across oceans.

Hanuman was fathered by the wind god Vayu, while Sun Wukong was born from a wind-impregnated stone egg. Flying mountains are significant in Chinese Buddhist tradition, while the Ramayana Hanuman flew, carrying a mountain, to fetch healing herbs.

A third possibility is that the Monkey King legend originated from Buddhist traditions and was later influenced by Hindu myths and Chinese folklore. Monkeys feature prominently in Buddhist Jatakas, and two—Tayodhamma Jataka and Mahakapi Jataka—involve Monkey Kings.

Orientalist Richard Gombrich speculates that the Ramayana may have spurred a Buddhist counter-story in the Dasaratha Jataka. Interestingly, Buddhist tradition presents Ravana, the villain of the Ramayana, in a positive light, with texts like the Lankavatara Sutra depicting the Buddha teaching Ravana. In this context, Chinese storytellers may have merged Buddhist and Hindu traditions by equating Ravana with the Jade Emperor and Hanuman with the Monkey King.

Scholars such as Hera Walker have revised the Ramayana-origin theory, proposing that although Chinese folklore contributed to Sun Wukong’s development, Hanuman provided the initial inspiration. The spread of Indian culture through the Maritime Silk Road likely facilitated the transmission of Ramayana mythology to China, with the southern Chinese port of Quanzhou playing a key role.

The Maritime Silk Road

The Maritime Silk Road connected East Asia, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian Peninsula, East Africa, and Europe. Originating from earlier jade and spice networks about the 2nd century BCE, it prospered until the 15th century CE.

Despite its name, the trade network dealt with commodities other than silk – high-value textiles, jade, spices, aromatics, porcelain, ivory and gems, as well as lower-value grain, wine, wood, metals, ceramics and manufactured goods. A variety of merchants engaged in trade on the sea route, including Arabs, Chinese, Persians, Tamils, and Austronesians of Southeast Asia.

Sri Lanka probably served as an entrepôt on the route, shortening the time the monsoon-dependent merchants had to spend traversing from East to West and vice-versa; most would concentrate on the sectors either to the East or to the West of the island. While Sri Lankans do not appear to have been major players on the route, the 9th century Tang dynasty scholar Li Zhao, in his Guo Shi Bu (Supplement to the history of the state) did mention that “the ships of the Lion Kingdom are very big, from top to bottom, their ladders make many zhang” (the Lion Kingdom being Sri Lanka and a zhang being 3.58 metres).

During the 15th century, a Sri Lankan “prince” settled in Quanzhou, probably due to the city’s climatic similarity to the Sri Lankan lowlands. His 19th-generation descendants, belonging to a family called Shi, still live there.

Quanzhou

Quanzhou is a port city on the north bank of the Jin River, beside the Taiwan Strait in southern Fujian. It was China’s major port for foreign traders during the 11th -14th centuries. Both Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta, who knew it as Zaiton, praised it as one of the most prosperous and glorious cities in the world. It became a cosmopolitan centre, home to settlements of merchants from many lands. This led to a mixing of cultures, religions and languages.

UNESCO added “Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China” to its World Heritage List in 2021, due to its crucial role in medieval maritime trade, its unique blend of Buddhist and Hindu temples, Islamic mosques, and Christian churches and its rich archaeological heritage.

In the Licheng district of Quanzhou is the Kaiyuan Temple, a Tang-dynasty monastery built about 685. The largest temple in Fujian province, it covers an area of 78,000 square metres, within which it holds several image houses and two large pagodas.

Behind the main image house, the “Mahavira Hall”, are columns inscribed with Hindu-style figurines of deities, wrestlers and other scenes (resembling the carvings on the wooden columns at Embekke Devale in Kandy). These, and 300 similar carvings dispersed throughout Quanzhou, originally belonged to a Hindu temple consecrated in the 13th century. Tamil merchants established the temple, but many of the sculptors appear to have been Chinese, carving Hindu figures in the local style.

Cultural diffusion

West of the Mahavira Hall lies the Renshou (or Western) Pagoda, completed in 1237. The octagonal, 44-metre stone pagoda structure has five storeys, each adorned with sixteen relief carvings. On the fourth storey is a carving of a muscular, sword-wielding, monkey-headed warrior; scholars consider this the earliest representation of Sun Wukong.

It resembles a carving of Hanuman from the12th century Panataran temple in Java and may be seen as a transitional form between the Hindu deity and the Buddhist saint. As such, it illustrates graphically the process of cultural diffusion which took place along the Maritime Silk Road.

This network of sea routes facilitated not just trade, but the spread of ideas, technologies, and cultural practices. Such religions as Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam spread along these routes, influencing local cultures, while art and architecture saw cross-cultural influences, such as Chinese porcelain shaping Middle Eastern pottery styles. Literary and linguistic exchanges occurred, with Sanskrit influencing Southeast Asian languages. Technological innovations, including the compass and papermaking, travelled west, while Chinese scholars benefited from Islamic astronomical knowledge. This cultural diffusion enriched societies and laid the foundation for global interconnectedness.

The legendary hero of Journey to the West, and his transformative journey from chaos to enlightenment, reflects the blending of multiple cultural and religious influences. He stands as a symbol of the harmonious integration of diverse traditions, embodying the peaceful exchange of ideas between different civilizations in the ancient world. He exemplifies the possibilities inherent in the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road of today.

Vinod Moonesinghe read mechanical engineering at the University of Westminster, and worked in Sri Lanka in the tea machinery and motor spares industries, as well as the railways. He later turned to journalism and writing history. He served as chair of the Board of Governors of the Ceylon German Technical Training Institute.

Factum is an Asia-Pacific focused think tank on International Relations, Tech Cooperation, Strategic Communications, and Climate Outreach accessible via www.factum.lk.

The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the organization’s.